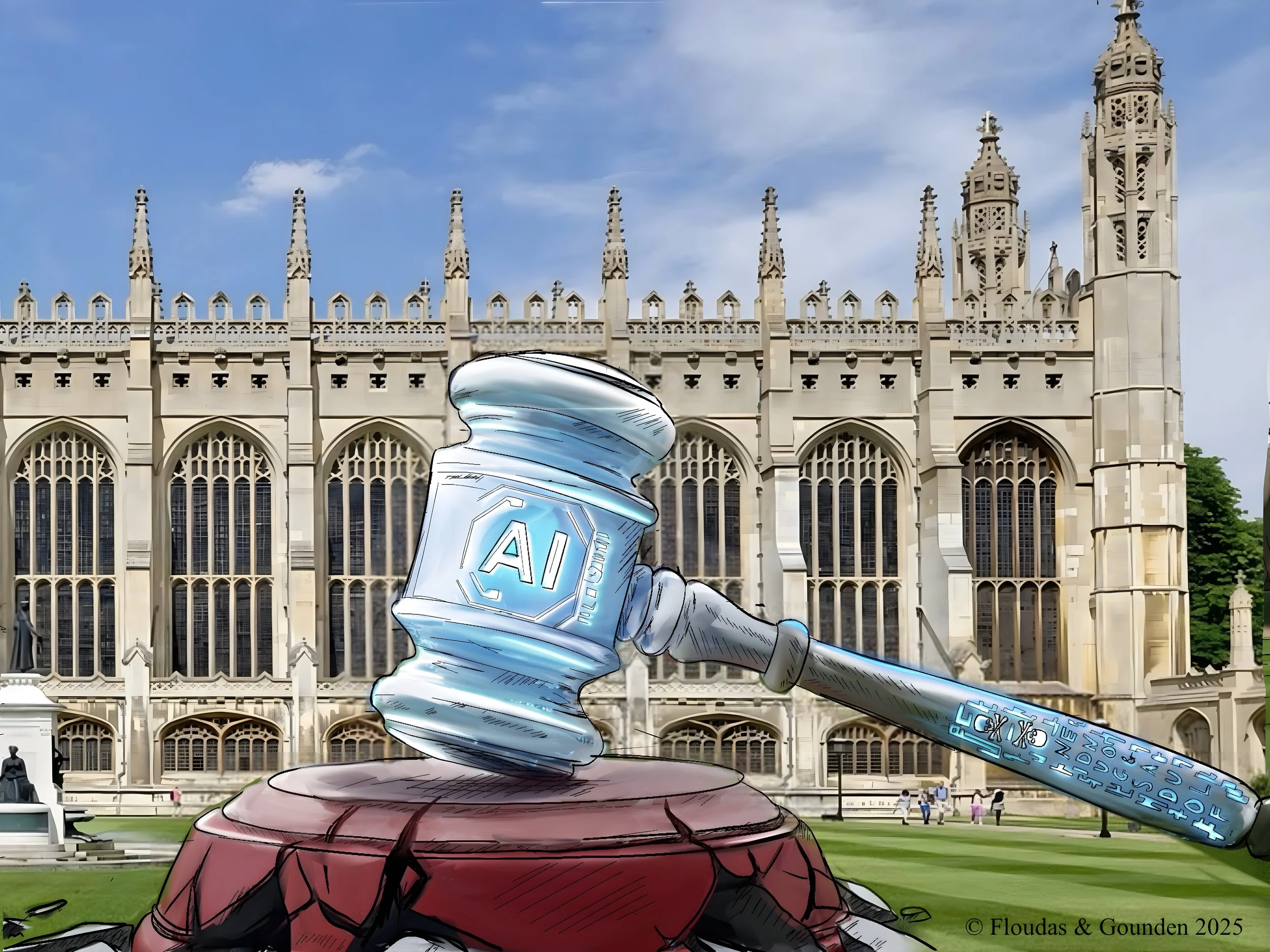

‘Therefore the law is slacked, and judgment doth never go forth’*: Considerations of AI adjudication via LLMs

Written by Demetrius Floudas

Original Graphics created by Zara Gounden, New York University

Sitting in my Cambridge office, surrounded by the trappings of a centuries-old institution, I am reminded of the profound changes that are sweeping through the world. ‘Mankind’s last invention’[1] has burst well out of its bottle in the last couple of years and is stealthily making inroads into matters hitherto reserved exclusively for non-machine agency. Intellectual labours, cultural expression, amorous relationships, and metaphysical inquiry, are already within that multifarious genie’s ambit.

In what regards the legal profession, the integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) has been surprisingly swift and transformative. The systems in use have demonstrated the ability to generate legal documents, provide law advice, and even predict the outcome of some cases with a degree of accuracy. Such developments have inevitably led to speculation that AI could one day replace not only advocates but also magistrates. The question is not whether artificial intelligence can rule on us—it already does, in credit scores, hiring algorithms, and predictive policing. The real issue is whether we are prepared to let it judge for us. Without much debate or deliberation, it is now assumed that AI will play a role in the legal system, and the only concern remains how far that will extend.

But why indulge in this discussion about AI judges, has anyone already advocated for them?[2]

The primary focus of the debate around LLM impact on the legal profession has thus far concentrated on the repercussions to law practitioners. Attorneys, however, are only auxiliaries in the adjudication process; justice, the concrete application of law to human disputes and behaviour is in concreto dispensed by the judiciary. It is the courts, not the law firms, that embody the final authority of the state’s legal power.

In fact, in most countries, society regards the courts more highly than the other two powers of the Montesquieu tripartite. At the very least, they go through extreme lengths pretending to. Of the other two powers, the legislature is usually fair game; as for the executive, there is open season for it from day one. In authoritarian regimes, a similar situation is reflected by the slow but recurring turn-around and replacement within the ranks of parliament and government (bar the elite top of the pyramid), whilst frequently exhibiting a peculiar, if cynical, stability in their judiciaries.

There is already a plethora of AI models that law firms deploy to draft briefs, sift through thousands of pages of documents, and submit motions. At the same time, hundreds of new apps bring AI-driven legal advice and democratise access to counsel; individuals who once could not afford a lawyer now consult chatbots for guidance. Nevertheless, the natural culmination of the cosmogony taking place in the ranks of lawyers globally by means of this ‘cheap justice for everyone in their pockets’ scheme would be the production and procedural introduction of millions of cases for which there will no longer be any barrier to entry, either money or time.

Today’s courts, already groaning under the weight of enormous caseloads, will suddenly face an avalanche of new computer-processed disputes. The decision-making system, creaking and barely holding as it is, would not merely buckle under the strain—it would shatter entirely, via an unprecedented inundation of every judicial structure on the planet and their complete failure to cope with the sheer volume of litigants, claims, counter-motions and deposited documents. The backlog of cases would stretch to decades, and the wheels of justice, which turn with agonising slowness now, would grind to an irreversible halt.

This is the real-life nettle that events like eLab’s LLM x Law must grasp. Their well-meaning intent is to incubate dozens of shiny, ‘transformative’ AI-based legal apps; programmes that can perform, almost gratis and in mere minutes, tasks that once demanded the expensive and time-consuming labour of trained professionals over days or weeks. The bright and industrious participants of the hackathon, mesmerised by the ideal of making justice more accessible to everyone, create AI systems which unilaterally facilitate (or even completely bypass) the frantic toil of time-constrained advocates.

However, like the proverbial Sorcerer’s Apprentice, participants and supporters may not recognise the unintended consequences of what they have wished for. Unwittingly, they largely fail to consider the implications of naively accelerating one part of an intricate system whilst the rest remains unchanged.

With the daily introduction into the court organisation of thousands of disputes that would have never seen the light of the day if it were not for the free apps that such hackathons aim to produce, the choice will become stark but simple:[3] either we disallow these digital aides and continue with the way things have been done for millennia, or we introduce adjudication mechanisms presided over by AI – a set of ‘AI judges’.

The result of the latter is an unorthodox legal process: Advocacy LLMs prepare, compile and submit all requisite documentation on behalf of the human parties, that are in turn analysed, evaluated and adjudged by dispute-resolving LLMs, functioning as arbiters. The silicon magistrate renders its verdict, returning it to the humans whose fate it decided. Are we really ready for this?

The idea of replacing human magistrates with silicon ones may prima facie appear outrageous, but we have seen how the proliferation, accessibility, and low cost of AI-based legal services will rapidly trigger an exponential increase of the volume of juridical caseload worldwide. The advent for AI adjudication, however, is not a result of popular demand; no crowds gather demanding robot judges. It is, instead, the natural corollary of the enthusiastic expansionism of the technology sector, eager to optimise another human sphere; and by a managerialist outlook that occasionally confuses speed with quality, and process with purpose. The same machine learning drivers that are democratising legal services will ultimately necessitate the mechanisation of the bench. Society cannot simultaneously embrace unlimited legal accessibility and maintain human-scale judicial systems.

Will this inevitability make machine adjudication become acceptable to us then? This would doubtlessly constitute the ne plus ultra attainment of Artificial Intelligence in the area of Law. But will humanity be a net winner or loser of such a defining social contract transformation? Could there be some intermediate solution to somehow reconcile such tensions?

In Part II of this essay, we shall consider these questions and attempt a prediction of whether adjudication by Artificial Intelligence could ever, and should ever, become acceptable and widespread.

*Habakkuk 1:4.

[1] I. Good, ‘Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine’, (6) Advances in Computers, 1965, 31–88.

[2] Kim & Peng, Do we want AI judges? The acceptance of AI judges’ judicial decision-making on moral foundations. AI & Society (2024).

[3] Baryse & Sarel, Algorithms in the court: does it matter which part of the judicial decision-making is automated?, 32 (1) Artificial Intelligence and Law, 2024, 117-146.

Demetrius Floudas is a practicing Advocate; Visiting Scholar in AI Governance at Downing College, Cambridge; and member of the AI@Cam Unit. He is an Artificial Intelligence policy-maker & regulatory strategist; he has contributed to the drafting Plenary and WG2+3 of EU AI Office’s Code of Practice for General-Purpose Artificial Intelligence; the UNESCO Guidelines for Use of AI in Courts & Tribunal; the OECD risk thresholds for advanced AI; and is the Editor in the ‘AI & Law’ Section of the PhilPapers academic repository. Demetrius is also Adj. Professor at the Law Faculty of Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University in Kaliningrad, where he lectures on Artificial Intelligence Regulation; Fellow of the Hellenic Institute of Foreign and International Law; and AI Expert at the European Institute of Public Administration. He previously served as Regulatory Policy Lead of the Global Trade Programme at the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and as head of the scientific team preparing the revision of the Civil Code of Armenia. In his spare time, he provides commentary to a number of international think-tanks and organisations, with his views frequently appearing in media worldwide.

Original Graphics created by Zara Gounden, New York University